The story of Tahitian Pearls in French Polynesia

PEARL PRODUCING SHELLS OF THE WORLD

Not all shells produce pearls, but quite a large number of bivalves are capable of producing pearls of different qualities. Even mussels raised only to end up on the plates of seafood lovers can produce a tiny yellowish pearl, just as the giant clams of tropical lagoons can create “marbles” that have no real aesthetic value.

The most famous pearl producing bivalve is the Pictada fucata, (also known as akoya) which creates the traditional white pearls of Japan. This shell can be found in the temperate and colder waters of Asia (Japan, China, Korea).

A small freshwater pearl-producing bivalve, which can be easily farmed in Asia, Hyriopsis schegeli, has enabled Japan, and especially China, to flood the market with small, low-priced pearls ranging from cream-colored to pink, and including yellow-gold tints.

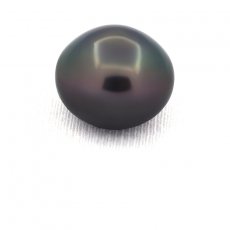

Pinctada margaritifera, which produces the Tahitian Pearls, can be found throughout the Pacific. An adult shell (lifespan from 15 to 30 years), can weigh up to 5 kilos.

Pinctada maxima are the largest of all: a cousin of the Pictada margaritifera, it can weigh more than 5 kilos and produces the famous “South Sea pearls”, especially in Southeast Asia and in the Broome region of Australia. (creamy highlights, pink and pale pinks).

Another beautiful pearl shell, which has a wing shape, and is well-known for its creation of “mabe”, is the Pteria penguin, commonly found in Asian seas, especially in Thailand near Phuket.

Pinctada maculate: it is well-known by its Polynesian nickname of “pipi”, a small shell producing tiny gold-colored pearls, the “poe pipi”. It is a mini-shell, compared to the Pinctada margaritifera, and lives in the same biotope.

Species of bivalves used in pearl farming

Pinctada Margaritifera -

Pinctada Margaritifera -  Pinctada Maxima -

Pinctada Maxima -  Pinctada Fucata

Pinctada Fucata

Pinctada Martensi -

Pinctada Martensi -  Zones of pearl production

Zones of pearl production

PINCTADA MARGARITIFERA

The “pearl oyster” of French Polynesia is misnamed, because the animal, Pinctada margaritifera by its Latin name, is a large mother-of-pearl producer, belonging to the family Pteridae, reputed throughout the world for its high quality mother-of-pearl secretions. Pinctada margaritifera, which we will call by its French name, nacre, to simplify this explanation, is among the giant shells of tropical seas, because an adult may grow to 30 cm (1 foot) in diameter, and weigh over 5 kg (11 pounds).

Certain specimens of this nacre, also known as “black-lipped pearl oyster”, can even weigh up to 9 kg (20 pounds).

The nacre lives most of its life in the lagoons, but can also be found in the ocean. In the Marquesas Islands, for example, where the islands are not bordered by reefs, the nacre proliferates in the wild, and attaches itself to the rocks. Because of its rough life conditions, it cannot grow as large there as it can in the calm of the lagoons.

A strange particularity of the Pinctada is its changing sex during its life, and also during times of stress.

We now know that when in its female stage, she produces eggs all year round, with two peaks at the changing of the seasons. It takes two or three years for a nacre to reach the maturity necessary to be able to reproduce. Only by creating an extraordinary quantity of eggs (tens of millions per animal), can the survival of this species be assured in its natural environment, especially because the spermatozoids meet up with the eggs only by accident for fertilization.

The larvae then become the prey of all plankton-eating animals. And even the shell, when it is young is the target of a number of carnivores, among which the trigger fish is the most feared by pearl farmers.

The fragility of the Pinctada margaritifera therefore necessitates constant care by those who take on the challenge of raising them.

THE FIRST CULTURED PEARL

A Japanese man, Kochiki Mikimoto, was the first person to develop the technique of grafting a nacre to produce a pearl. The first pearl harvested (in fact a mabe) was on July 11, 1893, in the Ago Bay in Japan.

However, another Japanese man, Tatsuhei Mise, is recognized by historians as the true father of this art, and obtained the first round pearl in 1904. Yet another Japanese man, Tokishi Nishikawa, discovered the secret at practically the same time, but it took several years for their techniques to become official: the two licenses of Mise and Nishikawa were registered in 1907.

In 1908, Mikimoto registered his patent; these three documents could be called the birth certificates of pearl grafting.

Mikimoto's original technique consisted of wrapping an artificial nucleus in a piece of tissue from the nacre, and sliding it all into another “oyster”.

This procedure is quite a severe surgical operation, and very traumatic for the nacre which receives the foreign body into its organism. Consequently, the mortality rate was high. Less traumatic procedures, consisting of inserting only a nucleus and a small piece of grafting tissue, caught on quickly, and in this sense Mise and Nishikawa were correct, because they were the discoverers of this technique. But it was their colleague who quickly realized the possibilities of this activity and he was the true promoter of the cultured pearl, first in Japan, and then throughout the world.

It is interesting to note that in 1914, Kochiki Mikimoto practiced his avant-garde work on a little-known nacre, the Pinctada margaritifera.

But in fact, just what is a “natural” pearl, and what is a cultured pearl?

When we refer to a natural pearl, we mean a small sphere of calcium carbonate, or aragonite to be more precise, formed by a bivalve when a foreign body is introduced into its tissue.

The intruding particle may be a grain of sand, or something else which bothers the animal. Its defensive reaction is to secret a fine layer of aragonite, which is the same as its shell, around the particle to isolate it. This secretion is accompanied by a constant rotation of the particle, which results in its generally round form.

The cultured pearl, on the other hand, is the result of human intervention on a bivalve. The grafter artificially introduces a foreign body into the animal, with the idea of compelling it to put its defense mechanism into action, to isolate the intruder by enveloping it in the aragonite. The little marble which is artificially introduced is called the nucleus, and is generally inserted with a tiny piece of tissue from another nacre. After this grafting, the aragonite secretion begins.

The composition of the pearl is 90% pure aragonite. If the pearl and the mother-of-pearl have such different appearances in the light, it\'s simply because the secretion is done spherically in one case, and horizontally in the other. This covering of fine layers of aragonite (there are at least a thousand layers on a high-quality pearl) permits the light, whether sunlight or artificial, to interplay with the micro-crystals of aragonite, and this determines what we call the orient of the pearl.

Without getting too technical, we must remember that a “natural” pearl and a “cultured” pearl are both natural pearls formed by a bivalve. They are in no way “artificial pearls”, which are not formed by the natural process of a bivalve. The essential difference between “natural” pearls and cultured pearls is that the cultured pearls have a nucleus, which can be detected by an x-ray machine if the owner of the pearls has any doubts. In olden times there were often doubts about the origins of pearls, but in modern times, in the world market, “natural” pearls have all but disappeared.

BACK IN THE DAYS OF THE PEARL DIVERS...

We often hear the term “pearl oysters”, which is incorrect, because the molluscs which form the pearls destined to become French Polynesian jewelry are the great Mothers-of-Pearl, “Pinctada margaritifera” being their Latin name.

In ancient times, these “nacres” were used by the Polynesians, the first colonizers of the South Seas. Some had utilitarian value, of course, but others had ornamental and decorative value. Ancient ceremonial costumes were adorned with large polished mother-of-pearl shells with shining golden reflections, no doubt adding to the majesty of those who wore them.

And in fact, throughout history, mother-of-pearl shells have always intrigued humans, not only for the pearls which they may contain (it is said one pearl for every 15,000 nacre) but for the beauty of the shells themselves.

In more recent times the mother-of-pearl shells have been used as shirt buttons as well as having many other functions (inlays, musical instruments, etc…) We can find in the archives of Polynesian history accounts of harvesting nacre since the beginning of the 19th century; the first boat reported in this commerce was the “Margaret”, which transported a shipment of nacres from the Gambier Islands to Australia in 1802. The demand did not cease to grow, the number of ships and their voyages between San Francisco, Valparaiso and Sydney multiplied during many years, in the most perfect anarchy, because it took until the end of that century for the French Administration to decide to control this “savage” activity.

Using a piece of cloth or various trinkets from modern society, a knife, a wire, or a cotton sack, it was easy to get tons of shells, and in fact, this manner of harvesting, a virtual rape of the natural resources with no notion of managing the supply, continued until after the second world war. Meanwhile, around 1870 the Doctor Bouchon-Brandely, sent by the French government to study this raw material, sounded the alarm by warning that the lagoons would eventually become deserts; in the beginning of the 19th century, some visitors had commented that they had difficulty walking in the shallow waters, there were so many sharp mother-of-pearl shells everywhere. But in the beginning of the next century it had become necessary for divers to descend deeper and deeper to find sufficiently large shells.

At that time, the method of diving was like something out of legends: divers descended sometimes over 40 meters deep, with 8 kilos of lead ballast. A pair of glasses, a glove and a net were the only equipment for these adventurers who faced not only moray eels and sharks, but also diving accidents, like the famous “vana taravana” or rapture of the deep, which caused them to lose their minds.

With these high and low points in production as well as prices, what was known as “the dive” continued until the 1960s, although the invention of plastic buttons, in 1957, signaled the end of this activity.

Before the first world war, annual harvests rarely attained 600 tons; between the two great wars, they sometimes exceeded 1200 tons (1350 tons in 1924: waterproof goggles, the ancestor of diving masks, had been invented), but the harvests diminished to under 1000 tons per year after the second war (500 to 800 tons average) to finally end up at…2 tons in 1979. The Tuamotu and the Gambier archipelagos had been under the most severe regulations, but the destruction of the resource resulted in quotas per atoll, strictly implemented dates when diving was permitted, years when diving was prohibited (one season of diving every 4 years), and sectors with no diving, veritable “reserves”.

Faced with these dramatic losses, from the beginning of the 20th century experimentation began, not with reproduction, but with collecting “baby nacres”, or “spats”, but the uncontrolled pillage brought in so much money that a general lack of concern reigned.

In 1954, the situation had become so urgent that the government's Fishing Department finally decided to follow the recommendations of former specialists: the practice of gathering the spats on branches of miki-miki, a small bush from the Paumotu shorelines, was revived on several atolls, and if the results were not extraordinary, one may say that without a doubt these empirical efforts saved the species from extinction.

As there was no connection to the harvesting of the shells, capturing the spats did not cause much enthusiasm among those who made their livings from the mother-of-pearl, because it required medium- to long-term planning, hardly a local tradition; but maintaining this resource mobilized enough energy to increase the numbers of nacres for the seventies, when pearl farming began.

Pinctada margaritifera had not been very far from extinction. Thanks only to the tenacity of the rarely-aided or recognized early researchers during the first decades of this century, the bivalves number in the millions today. Cultured pearls, because of the era of pearl diving, risked never even seeing the light of day…

Takapoto, Manihi, the Gambier Islands, Marutea are atolls where the capture of the spats have had excellent results, thus permitting the rebirth of the pearl business, thanks to those natural resources that were not completely depleted. But it was a close call!

THE FIRST PEARL FARMS IN THE TUAMOTUS

The rescue of those last mother-of-pearl bivalves in the lagoons of the Tuamotus coincided with an increase in the interest for the pearls that the Pinctada margaritifera had formerly rarely produced. In fact the ancient Polynesians, lacking the tools to drill or work these natural curiosities, did not place much value in them.

It was a curious Frenchman, a veterinarian named Jean Domard, who continued the work of his predecessors by immersing himself in the Japanese techniques of grafting, in the early sixties. The director of the department of Fishing, he became rapidly convinced that exceptional pearls could be obtained from Polynesian nacres. He worked incessantly, and in 1965 he made a test harvest: Polynesian cultured pearls saw the light of day for the first time that year, a light that they eclipsed by their sumptuous lustre.

Jean Domard succeeded, thanks to a Japanese grafter whom he had the wisdom to bring from Australia, after having failed time and time again in his attempts to graft the nacres himself.

It was an adventurous and enterprising local journalist, Koko Chaze, who would cross the path of Domard and launch himself into the fabrication of half-pearls. Koko Chaze set himself up in Manihi, where he would change the destiny of that atoll, and made his first harvest one year later.

At the same time, a family of Parisian jewelers, the Rosenthals, discovered the harvest of Jean Domard; the father had the pearls officially recognized by the Gemological Institute of America, and his two sons became associates of Koko.

THE « BLACK GOLD » RUSH

The success of these first pioneers of pearl faming created a lot of jealousy and a lot of imitators.

In fact, pearl farming would literally bring life back to certain atolls in the northern Tuamotus, which had suffered dramatic depopulation, (many inhabitants had been drawn by the bright lights of Papeete) before the development of this new activity.

This was the case, for example, in Takaroa and Takapoto in the northern Tuamotus, but in many other small atolls as well, where the number of maritime concessions literally exploded in the 1980s: Hikueru, Fakarava, Kauehi, Makemo, Anna, Ahe…many atolls mobilized their energies to produce pearls.

The end of trial and error techniques, prices at their highest, everything contributed to the skyrocketing demand of maritime concessions: over 800 at the end of the 1980s, more than 2,000 in 1990 and 1991.

The collection of oyster larvae (for the lagoons which lend themselves to this) and grafting are two completely different aspects of the pearl industry, because certain lagoons are very well situated for pearl production but on the other hand have hardly any nacres.

This is why, in the heart of the Tuamotus, there is endless transporting of young nacres, by boat or by plane, operations which are not without danger for the ecological balance of the lagoon environment:

The spread of epidemics and high mortality rates in many colonies of oysters, before or after their grafting, were the result of viruses being too widely diffused too quickly.

Uncontrolled competition logically ended up in a completely disorganized market, too many small pearl producers heavily in debt, having dumped all of their production (often of mediocre quality) on a too-limited number of buyers.

The law of supply and demand began to balance the situation, many pearl farms having ended in failure.

The official statistics of 1997 concerning the number of maritime concessions accorded stated that 2,010 collection concessions, 1,603 oyster raising concessions and 1,328 grafting concessions were authorized that year, or a total of 4,941 concessions. This does not represent the total number of pearl farms in activity, as many farms are authorized for all three activities.

Nevertheless, we can estimate that there are over 1,000 pearl farms engaged in pearl production at the moment, mostly in the Tuamotu-Gambier archipelagos.